The most imposing stone centipede you’ll find in the eastern US is the charismatic Bothropolys multidentatus (Lithobiidae: Ethopolyinae). Exclusively found in dead wood microhabitats, it’s a gorgeous chestnut-brown to orange centipede that reaches lengths of up to 30 millimeters—a true beast! There are only a few other lithobiomorphs of such size in our area (really just limited to Lithobius, Eulithobius, Neolithobius, and Zygethopolys).

Live Bothropolys multidentatus under my microscope.

It’s one of our two eastern Ethopolyinae, the other being Zygethopolys atrox. Both are immediately separable from other Lithobiidae and Henicopidae by the ventral pore fields on their posterior coxae: species in the Ethopolyinae have multiple rows of pores, rather than a single row.

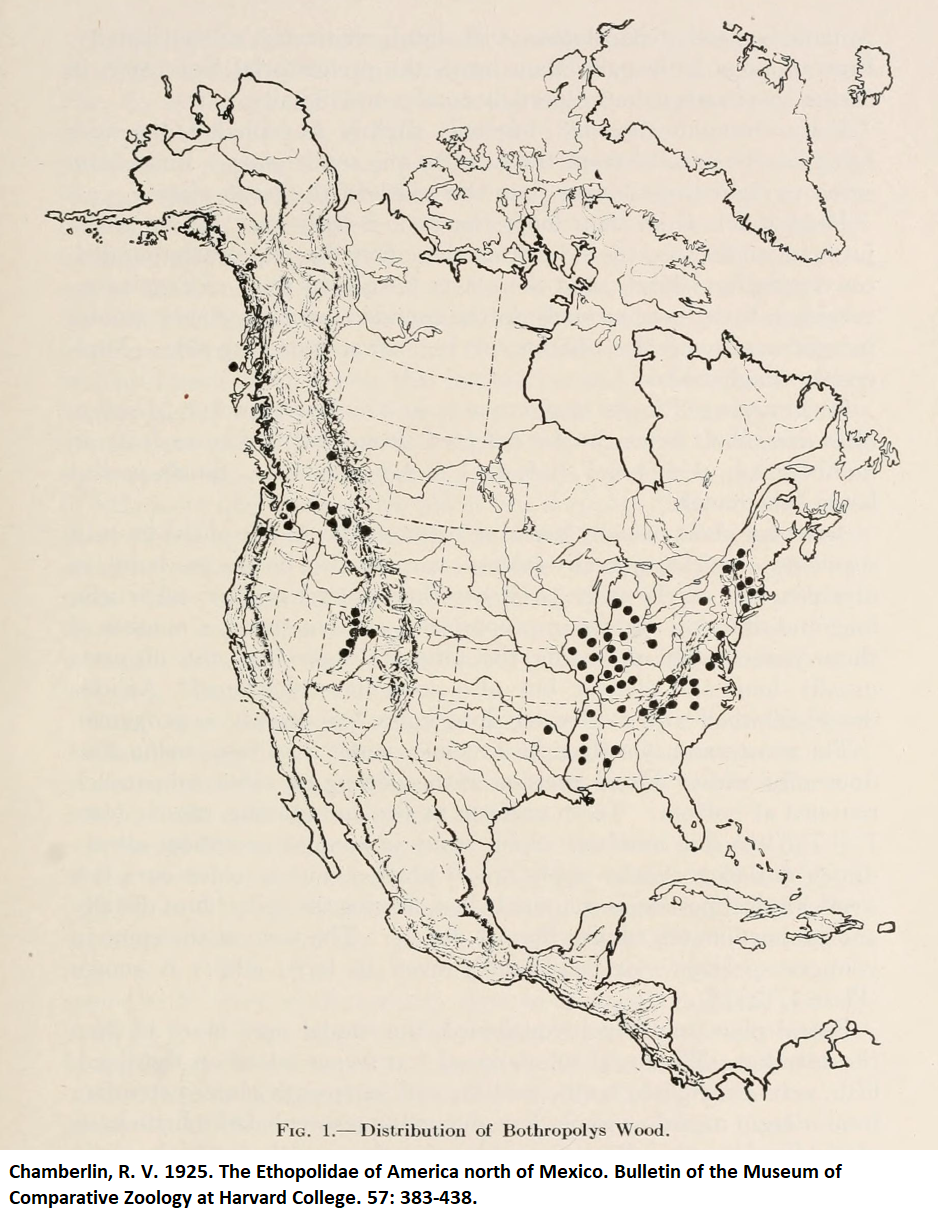

Within eastern Ethopolyiinae, B. multidentatus is widespread, while Zygethopolys atrox is only known from Cumberland Falls State Park in Kentucky. So if you find a stone centipede with multiple rows of coxal pores, it’s likely to be B. multidentatus. The map below shows the distribution of the genus Bothropolys, and all the eastern dots represent B. multidentatus.

As the species name indicates, B. multidentatus has a large number of prosternal teeth. The exact number is variable, ranging between 6 and 9 teeth in adults. At the lateral edges of the prosternal teeth, there’s a stout seta called the porodont. In Z. atrox, the porodont is inserted in the line of prosternal teeth, separating an outer tooth from the inner line of teeth.

Forcipular coxosternum of Bothropolys multidentatus,. Notice the stout porodont at the outer edge of the prosternal teeth. This specimen has 6+6 prosternal teeth.

Something that caught my eye recently is the production of the tergites in B. multidentatus. In the Lithobiomorpha, some species have triangular projections at the posterior corners of the tergites. When those projections are present, the tergites are said to be produced. When they’re absent, the tergites are not produced. In the first photo on this post, you can see that tergites 6, 7, 9, 11, and 13 are produced. This matches how Chamberlin (1925) describes the tergites. However, if you look at tergite 4 in my photo, you can see it’s also produced. I checked a few of my other photos and noticed some variation in the production of tergite 4, so I went on to check all the specimens of B. multidentatus in my collection. All my specimens are from the northeastern United States, so I was only able to check specimens from a small part of the range (Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Virginia).

I noticed three different character states for the 4th tergite: not produced, slightly produced (small triangular projections), and fully produced (strong triangular projections). As I checked my specimens, I made notes and took photos to directly compare later. I examined 29 specimens in total; here’s a map of the character states for all my specimens:

Distribution of Bothropolys multidentatus specimens from my collection. Dots are color coded by the character state of the 4th tergite: not produced, slightly produced, and produced.

After making the map, I organized the photos that I took and compared them to my written notes. I wasn’t completely satisfied with how I classified some specimens as having only slightly produced 4th tergites vs. produced, and concluded that I should simply categorize the specimens as having 4th tergites not produced or produced (including slightly produced). Here’s a comparison between the three states to illustrate what I mean.

The difference between slightly produced and produced is small and subjective. Even more subjective is that sometimes, a specimen will have one side of the 4th tergite produced and the other side not! Eagle-eyed readers will notice that is the case in the photo used for the not produced category: the left side is produced, while the right side isn’t. Other specimens in the not produced category didn’t have this mutation, but those specimens didn’t show the character quite as nicely. At any rate, combining the slightly produced and produced categories gives this map:

Distribution of Bothropolys multidentatus specimens from my collection. Dots are color coded by the character state of the 4th tergite: not produced and produced.

There doesn’t appear to be a geographical cline in the production of the 4th tergite; specimens with both produced and unproduced corners occur throughout the distribution of my specimens. I didn’t find any differences by sex or life stage either, though most of my specimens were females. So, no big surprises from this quick look, but it’s useful to know that the 4th tergite is sometimes produced in B. multidentatus. That should also make it easier to identify the species from photographs.

My sample size and area was limited considering the large distribution of the species, so it would be interesting to examine specimens from the rest of the range. The species could also use a survey of the genetic variation among populations as well, given that it’s so widespread. It has the distinct advantage of being easy to collect: if you focus on downed wood, you’re likely to find specimens pretty quickly.

References:

Chamberlin RV (1925) The Ethopolidae of America north of Mexico. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College 57: 385–437. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2810159

Crabill RE (1953) A new Zygethopolys from Kentucky and a key to the members of the genus. (Chilopoda: Lithobiomorpha: Lithobiidae: Ethopolyinae). The Canadian Entomologist 85: 119–120. https://doi.org/10.4039/Ent85119-3